Education lies at the heart of a nation’s development, it shapes future generations, reduces inequality, and expands workforce/livelihood opportunities contributing to the economy. Yet, ensuring quality education for all, particularly within India’s vast and varied Government school system, remains a challenge.

Education lies at the heart of a nation’s development, it shapes future generations, reduces inequality, and expands workforce/livelihood opportunities contributing to the economy. Yet, ensuring quality education for all, particularly within India’s vast and varied Government school system, remains a challenge.

In this exclusive interview with Ms. Ratna Viswanathan, CEO of Reach to Teach, we explore the journey of a former civil servant who transitioned from the corridors of governance to the grassroots of the development sector, and how the transition shaped the mission of Reach to Teach in strengthening learning outcomes in Government school systems.

The interview explores how local culture, context-sensitive solutions and community knowledge are interwoven into curriculum design, the measurable outcomes, and the organisation’s evolving role in education as a holistic supply chain. It also highlights the importance of meaningful teacher training, the nuances of working across diverse geographies, and how the private sector can play a more grounded role in enhancing public education.

What inspired you to shift from the civil service to the development sector, and how has your experience in governance and strategic leadership shaped your work and impact at Reach to Teach?

One of the key reasons I decided to transition from the civil services to the development sector was that I had already spent two decades of working in the services and learned extensively about governance – its structures, processes, people management, and the strategic advantage of having a ringside view of how Government at large operates across the country. Audit, in particular, covers every Department of the Government, offering unique access and understanding to systems of every kind—be it commercial engagements, defence, telecom, railways—since we audited every rupee spent from the Consolidated Fund of India. After spending 21 years, one acquires a certain set of skills, and you realise these skills can be meaningfully applied beyond where they were learned. Besides, the development sector also gives you an opportunity to engage with people more closely than Government work leads you to or typically allows, except in exceptional circumstances like that of a District Collector—opportunities that are once in a lifetime. Mostly it is about policy being removed and I thought this would give me an opportunity to work and contribute more closely with people at a ground level and have a view of development from a much more engaged level.

From its early days in 2007 to its present- day of working with State Education Departments, how has the organisation grown and adapted to meet the needs of the Government school system ?

From 2007 to 2019, we spent a large amount of time engaged in the field at community and district level , schools, blocks, villages, panchayats, parents and School Management Committees. Engagement at this level gave us deep learning and insights into what the ground situation was with respect to Government schools. While India’s geographies are distinctly different and all the learning acquired may not have translated into other geographies, the fundamental knowledge is agnostic and extends itself well to other geographies.

By 2019, after over 12 years of working extensively in the field, we had acquired significant learning with a bottom-up perspective of how Government schools function, the challenges they face, and the critical role teachers play in shaping outcomes. With this foundation, we felt it was time to take this understanding to the next level and use it to look at teaching and learning from a top-down lens, since the bottom-up had already happened. One of the best ways to do this was to engage with the State Education Departments because it is important to understand the State’s priorities regarding education. It was through this strategic pivot, we started embedding ourselves with the State Education Departments which helped us look at education as a supply chain. The understanding we acquired over the years showed us that education isn’t bits and pieces and had to be built brick by brick, stone by stone from foundational learning all the way to board examinations. It also taught us that beyond education, children in these schools need other forms of support as most children came from vulnerable, low-income households , many of whom transition directly from school to work. This learning helped us design the future where we engaged with the Governments and viewed education as a supply chain. We realised each level needed strengthening, but there was also an understanding that while these levels together can form a Comprehensive Learning Transformation Programme, they can also be taken apart, since we did end-to-end solutioning to ensure each level was self-sustaining. As a result, we created the Comprehensive Learning Transformation Programme in a manner which is agile and adaptive. Most importantly, we have situated it within the cultural context of a particular State to ensure relatability for children, parents and teachers is much higher than using a cookie cutter product pushed onto everybody.

There is a strong emphasis placed on contextualising learning, how have you tapped into local culture to improve learning particularly in diverse and under-resourced settings?

One of the most important insights we had was that children learn best when they are able to relate to what they are being taught. To truly engage them, one should present them with familiar examples, local heroes and elements from their immediate environment. That is why we took local flora, fauna, stories and cultural references because that is what they have grown up seeing, hearing, touching and feeling. Children are naturally curious and our aim was to leverage that curiosity to enhance learning.

When we see low-resource settings, we say it is a relative statement because you make that in the context of schools equipped with all kinds of digital equipment, toys, things to play with and tactical things to learn with. However, if one uses one’s imagination, anything locally available can be used to lead to the same outcomes. We use local leaves, flowers, and household objects to demonstrate different principles of learning as for children, the focus is on what they are learning, not the medium. We leveraged the curiosity that children have by building our approach around what was already available within the geographies we were working in and rooted our content, design, training, frameworks and collaterals in the local culture and context of the concerned State for children to relate better.

Could you share some highlights of the reach and impact that Reach to Teach has achieved? Also, what are the key learnings that emerged from working in diverse regions like Gujarat, Haryana, Arunachal Pradesh, and Meghalaya?

Of the 124 million children enrolled in Government schools, our work currently spans four States, reaching 7.19 million children across 58,000 schools and supporting 319,000 teachers. We started off with Arunachal Pradesh as a new State, by implementing the full design of our programme as envisioned. Over time, we saw that the design actually worked, considering in a space of two years, the improvement of children’s performance in Board Exams improved significantly by 10% for Grade 10 and 12% in Grade 12. The ASER report showed that literacy and numeracy were up in the State, and in NITI Aayog’s SDG Index, the State moved from ‘Aspirant’ to ‘Performer’ status under SDG 4: Quality Education. These outcomes indicate that our design, our engagement model, and the way we worked with the system were effective.

At the heart of everything we do is intense consultation with stakeholders across the ecosystem from the top to the bottom, to ensure that everybody owns what we create, as it is co-created. Besides, what we have learned is that no two States are the same. Depending on the ask of the State – what the State Government aspires to in terms of where it sees education going, and what is available on ground in terms of teacher capability, teacher availability, teaching and learning material, we customise our solutions by assessing what is available on the ground, what the State Government envisions, and how best it can be brought together.

Teacher training and leadership development for head teachers are crucial components of your work. What strategies have you found most effective in ensuring long-term improvements in teaching quality?

One of our primary focus areas has been conducting teacher needs assessments, which involves consulting teachers extensively about what they think and requires giving them a sense of agency and making them feel a part of the system. We have approached this in two ways, in Gujarat for instance we conduct regular training sessions, where we consult teachers to understand what they feel they need to be trained in and then design the training modules accordingly. While, in Arunachal Pradesh, we have trained teachers to work on the transformative programme, which includes key elements driven entirely by the teacher. In that context, the teacher is fully responsible for implementation. So the model depends on the State and its specific needs. Although the NEP 2020 mandates 50 hours of teacher training, it needs to be meaningful, aligned with what teachers need, related to their work, and designed to ensure they derive real value from it.

From learning gaps to equity issues, what according to you are the critical roadblocks limiting access to quality education in Government schools—and how can they be effectively addressed?

There is dissonance in how schools approach learning outcomes. Although there is an overarching framework, without supervision, implementation varies from school to school,

depending on the individual perspectives of Head Teachers and local teachers. This lack of uniformity makes achieving learning outcomes a challenge. One effective way to address this is by bringing everyone onto the same page and in consultation, co-create a design owned by the system that ensures a certain amount of standardisation in terms of approach, content, and how teachers are trained to roll out that content. Once that happens, because you have standardized the larger mass, the scale creates momentum and the heft leads to learning outcomes being achieved, because there is a mass that stands behind it.

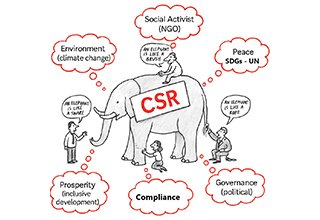

How can the private sector better support Government school education in a meaningful and scalable way?

The private sector should come together and directly engage with schools, teachers and not just the Government to understand real needs. They can help in many ways, not just through funding. It can support equipment, training, and creating facilities. Facilities doesn’t necessarily mean infrastructure considering if one is creating infrastructure, there is a need to build sustainability into the system so that it is maintained by the community and not something the private sector has to continuously manage. Similarly, it is also important to engage with players in the field who are driving learning and strengthening outcomes, and not just the established ones. Often, there are players doing exceptional work who may not have the visibility or market what they do. Scanning the ecosystem is something the corporate sector would find more helpful in driving greater value from the money they invest.